In the first half of 2025, amid historic and unprecedented events in the Middle East, Iranian journalists and media outlets experienced a highly turbulent and challenging period. During this time, the suppression of free information, which had taken on new and complex dimensions since Masoud Pezeshkian’s election as president, intensified.

Indicators of freedom of expression recorded an unprecedented decline, judicial and security crackdowns on journalists and media outlets surged, and the Islamic Republic escalated its transnational threats against Iranian journalists at an alarming rate.

The Defending Free Flow of Information (DeFFI) compiled its six-month report on the suppression of journalists and media based on 109 documented cases by its researchers. In the first half of 2025, DeFFI accounted for 27% of the total reports published from primary sources on press suppression in Iran. This report was published with the support of Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

Key Findings for the First Half of 2025:

- At least 95 journalists and media outlets faced a total of 110 instances of judicial and security crackdowns.

- At least 19 female journalists were subjected to prison sentences, judicial cases, or security measures.

- At least six journalists were detained.

- At least 46 new judicial cases were filed against journalists and media outlets.

- Judicial and security institutions violated the legal rights of journalists and media in at least 112 instances.

- “Spreading falsehoods” was the most frequently cited charge, attributed to journalists and media in 47 cases.

- A total of 22 years and three months of imprisonment and over 50 million tomans in fines were imposed on media professionals.

Chronology of the Suppression of Free Information in Iran

The suppression of free information in 2025 continued with patterns that had undergone tangible changes in 2024 following Masoud Pezeshkian’s election as president of Iran. A statistical comparison of judicial and security crackdowns on journalists and media between the first half of 2025 and the same period in the previous year revealed that security and judicial institutions increasingly resorted to threatening phone calls against journalists instead of summonses, filing judicial cases, or detentions.

Concurrently, the unlawful disconnection of journalists’ SIM cards, blocking of social media accounts without judicial orders, restrictions on social media platforms, intensified security pressures to remove critical posts, coercion of media outlet managers to prevent the production and publication of challenging reports, and the allocation of substantial financial resources to co-opt media and journalists into the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus were repeated with greater frequency.

The year 2025 began with at least nine journalists imprisoned in Iran. Nasrin Hassani in Bojnurd Prison, Zhina Modarres Gorji in Sanandaj Prison, Shirin Saeidi, Vida Rabbani, Saeedeh Shafiei, Rouhollah Nakhaei, Mostafa Nemati, Reza Valizadeh, and Cecilia Sala, an Italian journalist in Tehran Prison, entered the new year incarcerated. The number of imprisoned journalists at the start of 2025 increased by three compared to the same period in 2024, when six journalists were detained.

Over the first half of 2025, four imprisoned journalists, including Cecilia Sala, were gradually released. Meanwhile, Azhder Piri, editor-in-chief of the Pazhohesh Mellal monthly, was detained and transferred to Karaj Central Prison to serve a one-year sentence.

In the first month of 2025, the Islamic Republic of Iran launched a new wave of summonses, detentions, judicial case filings, and heavy prison sentences against civil activists and Iranian citizens, particularly ethnic minorities, across the country. Concurrently with this wave of suppression targeting citizens and activists, a new round of judicial and security crackdowns on Iranian journalists began. Within a single week, judicial and security institutions pursued at least five journalists through home searches, confiscation of personal belongings, summonses, and threats.

It appeared that these judicial and security measures against journalists stemmed from the Islamic Republic’s concerns over the potential for a new wave of public protests. Amid growing public dissatisfaction with Iran’s dire economic conditions, judicial and security institutions employed “preemptive suppression of journalists” to disrupt their professional duties, hinder citizens’ access to reliable and timely news, and reduce journalists’ influence on public opinion.

April 2025 coincided with the start of a new round of Iran-U.S. negotiations. These talks began less than two months after Ali Khamenei, the Leader of the Islamic Republic, stated in a meeting with air force and air defense commanders that “negotiating with America is neither wise, rational, nor honorable.”

Unlike in the past, when the Islamic Republic sought to prepare public opinion for shifts in its policies, this time it adopted an unprecedented approach to the negotiations with the U.S. A significant portion of the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus remained passive, while another segment reiterated Khamenei’s statements, publishing content opposing the negotiations. The promotion and justification of the need for negotiations with the U.S. were primarily carried out by media and political activists labeled as “reformists.” As Iran-U.S. negotiations began in Oman, Iran’s Supreme National Security Council issued a directive to the country’s media, prohibiting the publication of news from foreign sources and analyses regarding the negotiation process. Additionally, during the continuation of these negotiations in Rome, the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office filed charges against two media outlet managers for their critical comments on the talks.

The Press Supervisory Board also issued a written warning to the Ham-Mihan newspaper, which had published an article titled “The Impact of Strikes on Negotiations,” analyzing the effects of military clashes between Yemen’s Houthis and Israel on Iran-U.S. negotiations. The newspaper’s case was referred to the judiciary for prosecution.

During this period, the Islamic Republic used its judicial and security tools to conduct Iran-U.S. negotiations in secrecy and under a news silence, imposing extensive restrictions on the publication of independent news, reports, and analyses.

In late April, the Security Police summoned several journalists and active X platform users for posting critical content about Mahmoud Reza Aref, Iran’s First Vice President. These summonses and threats against journalists for criticizing Aref were the latest in a series of restrictions imposed by the vice president against media and journalists. A few months earlier, during the opening of the “Telecom 1403” exhibition, journalists covering communications and information technology were barred from attending due to Aref’s presence. In September 2024, following controversy over a photo of Aref’s son attending the introduction ceremony of the Minister of Industry, Mine, and Trade, several journalists reported on social media that the introduction ceremony for Sattar Hashemi, the Minister of Communications, was held without journalists’ presence, allegedly on Aref’s orders.

The restrictions and judicial-security crackdowns on journalists during Masoud Pezeshkian’s presidency were not limited to cases involving Mahmoud Reza Aref. According to an investigative report by the Defending Free Flow of Information (DeFFI), during the first 100 days of Pezeshkian’s presidency (July 28, 2024 – November 4, 2024), authorities, government institutions, and state-owned companies not only failed to withdraw many of their complaints against journalists and media but also filed new lawsuits. During this period, at least 38 new judicial cases were filed against media and journalists, with over 50% (20 cases) initiated by government institutions and officials. This trend of complaints by authorities and government institutions against journalists and media continued until the end of the sixth month of 2025.

Another significant event in the first half of 2025 that intensified the Islamic Republic’s judicial and security mechanisms for suppressing free information was the deadly explosion at port of Rajai. In late April, a massive explosion at a port in southern Iran resulted in dozens of casualties.

Within hours of the explosion, the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office issued a statement threatening journalists and media, urging “activists in virtual spaces and media to refrain from addressing issues that disrupt the psychological security of society.”

For days following the incident, non-governmental journalists and media were barred from the site, and the Islamic Republic monopolized news coverage of the explosion’s scope through its propaganda apparatus, particularly the state broadcaster IRIB.

Concurrently, the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office filed charges against several journalists and media outlets that published news and reports about the Bandar Rajai explosion. Others received “warnings.”

The prosecution’s filing of charges against media, media activists, and journalists is a recurring pattern for suppressing freedom of expression in Iran—a pattern that escalates exponentially following controversial events in the country.

Similar to the previous year, in the first half of 2025, the upward trend in media and journalist suppression showed a significant correlation with major social and political events in Iran. During this period, the most extensive suppression of free information in Iran coincided with the Iran-Israel conflict.

Unprecedented Disruption of Free Information Flow During the Israel-Iran War

On the morning of 13 June 2025, Israel launched extensive and unprecedented air, missile, and drone attacks on Iran. This assault began just one day after the expiration of a 60-day ultimatum issued by U.S. President Donald Trump to Iran for concluding Iran-U.S. negotiations.

Israel named its large-scale military operation “Rising Lion” and described it as a “preemptive strike.” On the first day of the war, Israel targeted multiple military and nuclear sites in Iran, killing several senior Iranian military officials, including Mohammad Bagheri, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, Hossein Salami, Commander-in-Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Amirali Hajizadeh, Commander of the IRGC Aerospace Force, Gholamali Rashid, Commander of the Khatam-al-Anbia Central Headquarters, and at least six other Iranian nuclear officials and scientists.

Concurrently, Ali Khamenei, the Leader of the Islamic Republic, released a video recorded in an undisclosed bunker, vowing that “Iran’s armed forces will render the vile Zionist regime (Israel) helpless.” Following Khamenei’s speech, the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus launched a campaign using key phrases from his speech, which expanded exponentially in the following days. State-controlled media in Iran widely used the term “terrorist attack” to describe Israel’s military operations.

From the outset of the war, Israel—unlike in the past—openly acknowledged responsibility for the attacks, releasing footage of airstrikes, videos of its commandos operating on Iranian soil, and details of its extensive military operations, deliberately aiming to gain the upper hand in psychological warfare. Simultaneously with its military assaults, Israel used media and propaganda efforts to undermine the image of a “stable” and “powerful” government that the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus had invested years in cultivating among Iranian citizens.

Israel gradually added targets to its list of attacks, which appeared to be selected more for their propaganda value and impact on Iranian public opinion. Attacks on Iran’s state broadcaster (IRIB) and Evin Prison were among these. These strikes resulted in dozens of civilian casualties. The attack on Evin Prison turned into a humanitarian disaster, with Iran’s judiciary announcing 79 deaths, while The Washington Post reported 49 fatalities, including 43 prison staff, two soldiers, and two children among the victims.

In response, the Islamic Republic mobilized its full judicial, security, and propaganda capacities to restrict the publication of unofficial news and cut off Iranian citizens’ access to independent information.

Within hours of the start of Israel’s attacks, Iran’s General Prosecutor’s Office issued a statement addressing media, journalists, and citizens, stating: “Appropriate legal action will be taken against those who disrupt the psychological security of society by publishing false content and spreading falsehoods.” Shortly afterward, the Cybercrime Division of the General Prosecutor’s Office announced judicial action against citizens who shared images or content related to Israel’s attack, labeling them “the enemy’s foot soldiers in cyberspace” and accusing them of undermining “the psychological security of the people.”

The Tehran Prosecutor’s Office established a “special task force” to address media, journalists, and citizens judicially and through security measures. This task force soon announced it had filed judicial cases against several Iranian citizens on charges of “disrupting the psychological security of society.”

Simultaneously, Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence issued a directive to media outlets prohibiting “predictions about the war’s outcome, collapse, reconciliation, nuclear attack, or economic downfall, as well as the publication of videos or images from explosion sites or affected areas.”

Iran’s prosecutor’s offices, amid the ongoing war, filed charges against at least eight media outlets and journalists, seized one news website, detained two journalists temporarily, issued warnings to several media outlets, journalists, and photojournalists, and continued a widespread wave of arrests targeting citizens who expressed opinions about the military conflict. This pattern mirrored actions taken in April 2024 after the IRGC’s missile and drone attack on Israel from Iranian soil (Vadeh Sadegh 1). Similarly, in early October 2024, following the IRGC’s second missile attack on Israel (Vadeh Sadegh 2), and in late October after Israel’s attack on military bases in Iran, the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office had filed charges against at least 12 media outlets, journalists, and media activists.

Alongside the wave of judicial and security crackdowns on journalists, media, and independent narrators in Iran, the country’s propaganda apparatus launched one of its most extensive campaigns of producing fake news and misleading narratives about Iran’s military operations against Israel through state media, pseudo-media, and affiliated social media accounts. From the early hours of the war until days after its conclusion, old videos, AI-generated content, and footage of incidents from other parts of the world were repeatedly republished by Iran’s state media as images of explosions, missile damage, and fires in Israel.

From the first hours of the war, Iranian citizens experienced severe disruptions in internet access. The Public Relations Office of Iran’s Ministry of Communications issued a statement announcing: “Temporary restrictions have been imposed on the internet. These restrictions will be lifted once the situation returns to normal.”

However, disruptions to international internet access in Iran peaked between 18 and 22 June. This level of disruption was unprecedented, to the extent that, except for a few security, military, and judicial media outlets (Fars, Tasnim, Mizan) using “tiered internet,” even some state and regime-affiliated media lost access to the international internet.

During this period, Iran effectively entered a media blackout. Amid the war, many Iranian citizens were deprived of access to reliable, timely, and essential information, leading to widespread confusion and ambiguity about events, and society faced challenges in analyzing realities and making informed decisions.

During the Iran-Israel conflict, known as the “12-Day War,” hundreds of civilians in both Iran and Israel lost their lives. Among them, three Iranian journalists were killed.

On the first day of the war, Fereshteh Bagheri, a reporter for the Defa Moghaddas News Agency, lost her life. Ms. Bagheri, the daughter of Major General Mohammad Bagheri, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, was killed alongside her father in an Israeli attack on their residence.

During Israel’s heavy bombardment of Tehran on 16 June 2025, the glass building of the IRIB’s Political Department, a symbol of Iran’s state broadcaster, was targeted by Israel, resulting in the death of Nima Rajabpour, a senior news editor at IRIB.

Hours later, Ali Pakzad, a reporter for Shargh newspaper, was detained by Iran’s security forces after visiting IRIB. According to the Shargh website, after hours of uncertainty about his fate, Pakzad contacted his family, confirming his detention by security forces.

On the same day, explosions from the bombardment of parts of Tehran damaged the buildings housing the newsrooms of Sazandegi newspaper and Ensaf News website. On the first day of the war, the bombardment of Tehran also damaged the Gol-Azin printing house, which publishes Tejarat newspaper and various other magazines and publications. According to these media outlets, no journalists were harmed in these incidents.

Additionally, during the Iran-Israel war, Ehsan Zakeri, who had years of experience working with Mehr News Agency and the International Quran News Agency (IQNA), lost his life.

Fereshteh Bagheri, Nima Rajabpour, and Ehsan Zakeri were three Iranian journalists killed during Israel’s military attacks while working for Iranian media outlets. During the conflict, Saleh Bayramy, a graphic designer with a history of collaboration with National Geographic magazine, was also killed. According to sources from the Defense of Free Flow of Information (DeFFI), Bayramy died in Tehran’s Tajrish area due to shrapnel from a missile strike while returning from a work meeting.

On the tenth day of the war, the United States bombed Iran’s nuclear sites in Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. The following day, Iran fired 14 missiles at a U.S. military base in Qatar. On the twelfth day, through Trump’s intervention and Qatar’s mediation, a ceasefire was announced between Tehran and Tel Aviv.

After the ceasefire, Ali Khamenei, in his third video address since the war began, claimed victory for the Islamic Republic, stating: “Israel was nearly brought to its knees and crushed under the blows of the Islamic Republic.” This narrative became the central theme of the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus.

Simultaneously, following the 12-day war, the Islamic Republic intensified the security atmosphere in Iran, continued internet access disruptions, saw an alarming rise in arrests of citizens on charges of “spying for Israel,” witnessed an upward trend in executions, reached a peak in the expulsion of Afghan migrants from Iran, and the Iranian Parliament passed a bill titled “Intensification of Penalties for Espionage and Collaborators with Hostile Countries,” criminalizing various methods of sustaining the free flow of information in Iran.

Just days after the ceasefire, the month of Muharram began in Iran. With the start of Muharram, the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus took on new and unprecedented dimensions. “Maddahs” (religious eulogists), who had long been an influential part of the Islamic Republic’s propaganda machine, incorporated themes such as “homeland,” “Iran,” and Iranian nationalism into their elegies.

During and after the Iran-Israel war, judicial and security crackdowns on journalists and media were not limited to Iran. The Islamic Republic’s transnational threats against Iranian journalists and employees of media outlets abroad reached alarming levels.

Escalation of the Islamic Republic’s Transnational Threats Against Iranian Journalists

In the first half of 2025, the Islamic Republic’s transnational threats against Iranian journalists abroad increased to an unprecedented and alarming extent. During this period, numerous cases of detention, threats, harassment, and targeted restrictions against the families of Iranian journalists abroad were documented.

In the early days of 2025, Mehrdad Aladin, a documentary filmmaker and brother of Kourosh Aladin, a journalist with Voice of America’s Persian service, was detained after appearing at Evin Court in Tehran. Mehrdad Aladin spent 12 days in temporary detention.

Later, Voice of America’s Persian service reported security pressures from the Islamic Republic on the families of its employees. It stated: “The families of several journalists and collaborators of Voice of America’s Persian service in Iran have recently been subjected to intimidation and detention. Families in Iran have been threatened with ‘consequences’ if their relatives’ media activities with Voice of America do not cease.”

In mid-March, a New York court jury found Rafat Amirov and Polad Omarov guilty in a plot to assassinate Masih Alinejad, an Iranian-American journalist and activist. According to prosecutors, Amirov and Omarov, leaders of a Russian criminal group, were hired by the Islamic Republic to carry out the assassination.

In May, following a complaint by the IRGC Intelligence Organization, Iran’s judiciary filed a case with serious charges against Parviz Yari, a senior researcher at the Defending Free Flow of Information (DeFFI). The case involved multiple violations of the researcher’s rights. Despite over two months of proceedings, no summons was issued to Yari, and after the case was transferred to Branch 1 of the Zanjan Revolutionary Court, the judge repeatedly denied the lawyer access to the case file for preparing a defense.

Days later, British police announced that one of the objectives of three Iranian citizens previously detained in the UK was to monitor and identify journalists linked to Iran International television. On 17 May 2025, the UK Home Secretary issued a statement in response to the allegations, stating: “The police have confirmed that the foreign country referenced in these charges is Iran, and Iran must be held accountable for its actions.”

June 2025, coinciding with the Iran-Israel war, marked the peak of the Islamic Republic’s targeted threats against Iranian journalists abroad. Early that month, the BBC issued a statement expressing “deep concern over the harassment of BBC Persian journalists and their families,” urging Iranian authorities to “immediately end this campaign of intimidation and cease threats, violence, and psychological harassment against journalists.”

According to the BBC, “BBC Persian journalists, along with other Iranian journalists residing in the UK and other parts of the world, face serious transnational threats from Iranian authorities. These threats have consistently targeted their families in Iran, who have been subjected to an ongoing campaign of intimidation. The BBC has now observed an alarming escalation in arbitrary interrogations, travel bans, passport confiscations, and threats of property seizure.”

In late June, the BBC reported that during the 12-day Iran-Israel war, Iranian security authorities contacted the families of BBC Persian journalists, threatening them with “hostage-taking.” The BBC stated: “According to journalists recently affected, Iranian security officials have claimed in contacts with their families that targeting family members as hostages is justified during wartime. They have also labeled journalists as ‘mohareb’—a term meaning someone who wages war against God—an accusation that can carry the death penalty under Iranian law.”

Meanwhile, the Islamic Republic acted on its threat of “hostage-taking” the families of Iranian journalists abroad. The IRGC detained the family members of a female presenter at Iran International. On the ninth day of the Iran-Israel war, Iran International issued a statement reporting that the IRGC had detained the presenter’s father, mother, and younger brother, who were residing in Iran, to pressure her to cease working with the network.

In June, these transnational threats peaked, following a message from Reza Valizadeh, an Iranian-American journalist, from inside Evin Prison, exposing an IRGC Intelligence Organization security operation targeting journalists abroad.

In a message from Evin Prison, obtained by DeFFI through Valizadeh’s associates, the former Radio Farda journalist revealed that one reason for his detention by the IRGC Intelligence Organization was his refusal to accept a proposal to convince Iranian journalists abroad to return to Iran. According to Valizadeh, the IRGC offered him a substantial sum to deceive his colleagues at Persian-language media outlets abroad into returning to Iran.

Valizadeh further disclosed another aspect of the IRGC Intelligence Organization’s plot against journalists at Persian-language media abroad. He stated that the IRGC had requested information about the administrative and operational structure of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Persian service, including the number of employees, their names and positions, administrative hierarchy, and even a map of the Radio Farda building.

According to Valizadeh, who is currently serving a 10-year sentence in Tehran’s Great Prison, he was detained after rejecting all IRGC proposals, including establishing a media outlet supported by the organization, following a summons to a building near the Second Air Force Square in eastern Tehran.

Female Journalists Still at the Intersection of Suppression

While some patterns of suppressing free information in Iran show no evidence of gender-based discrimination, others directly target female journalists.

On 2 February of this year, the Scientific Deputy of Iran’s Presidential Office prevented Sousan Nouri, a journalist, from attending a press conference at this governmental institution due to mandatory dress code and hijab regulations. On the same day, security personnel at Tehran’s Evin Court (District 33 Public and Revolutionary Prosecutor’s Office) barred Alieh Motalebzadeh, a photographer and women’s rights activist, from entering the court for refusing to comply with mandatory hijab rules. In March, Iran’s judiciary filed cases against the organizers of the Tehran Province Journalists’ Association’s journalism award ceremony (Cheragh) and female journalists who attended the event without adhering to mandatory hijab regulations.

In the first half of 2025, the suppression of female journalists continued relentlessly, mirroring the previous year. Within just six months, at least 19 female journalists faced judicial and security crackdowns by the Islamic Republic. During this period, at least five female journalists endured threats or harassment from the Islamic Republic’s security institutions, and judicial cases were filed against 11 of them.

In the rulings issued over the past six months, Manda Sadeghi and Farzaneh Yahyabadi—under Article 134 of the Islamic Penal Code, which considers the most recent ruling in each case—were collectively sentenced to three years and nine months of imprisonment.

At the start of 2025, of the nine journalists imprisoned in Iran, six were women: Nasrin Hassani in Bojnurd Prison, Zhina Modarres Gorji in Sanandaj Prison, Shirin Saeidi, Saeedeh Shafiei, Vida Rabbani, and Cecilia Sala, an Italian journalist, in Tehran’s Evin Prison, entered the new year incarcerated.

Over the first half of 2025, Saeedeh Shafiei, Vida Rabbani, Nesrin Hassani and Cecilia Sala were gradually released from prison. Nevertheless, by the end of the sixth month of the year, half of the journalists still imprisoned in Iran were women.

Systematic Violation of Journalists’ and Media Rights

In the first half of 2025, the suppression of Iranian journalists and media outlets continued relentlessly. Similar to 2024, criticism of the Islamic Republic’s inefficiencies or the publication of reports on corruption within government institutions and officials was the most frequent issue leading to judicial and security crackdowns on journalists and media. Publishing reports or social media posts criticizing the Islamic Republic’s international and regional policies—particularly regarding Iran-U.S. negotiations and the Iran-Israel war—and reporting on the Bandar Rajai explosion were other prominent reasons for judicial case filings or security measures against journalists and media.

In 2025, political and press courts once again, in a targeted pattern, refused to handle some media and journalist cases, in violation of the Press Law, and these cases were primarily referred to Criminal Court II and Revolutionary Courts for adjudication.

Within just six months, at least 95 journalists and media outlets faced a total of 110 judicial and security crackdowns. At least 19 female journalists experienced prison sentences, judicial case filings, or security measures, and Mehrdad Aladin, Vahid Dalijeh, Ali Pakzad, and Majid Saeidi were among the journalists who faced temporary detention. In May 2025, judicial officers detained Azhder Piri, editor-in-chief of Pazhohesh Mellal monthly, to serve a one-year prison sentence and transferred him to Karaj Central Prison.

In trials held until the end of the sixth month of the year, 10 Iranian journalists were collectively sentenced to 22 years and three months of imprisonment, over 50 million tomans in fines, four years of travel bans, over six years of bans from social media activities, and one year of prohibition from press activities.

Among the heaviest sentences issued during this period, the Tehran Province Appeals Court sentenced Reza Valizadeh, an Iranian-American journalist held in Tehran’s Great Prison, to 10 years in prison and additional penalties. In March 2025, Branch 1 of the Abadan Revolutionary Court sentenced Manda Sadeghi, Farzaneh Yahyabadi, Arash Ghalehgholab, and Kourosh Karampour to a total of 10 years and six months in prison in an ambiguous case lacking fair judicial process.

In the first half of 2025, the Islamic Republic’s judiciary filed at least 46 new judicial cases against journalists and media outlets. Prosecutors were the complainants in nearly half of these cases (20 cases). Following prosecutors, government officials and institutions, and then individuals or private companies, ranked as the next most frequent complainants against journalists and media.

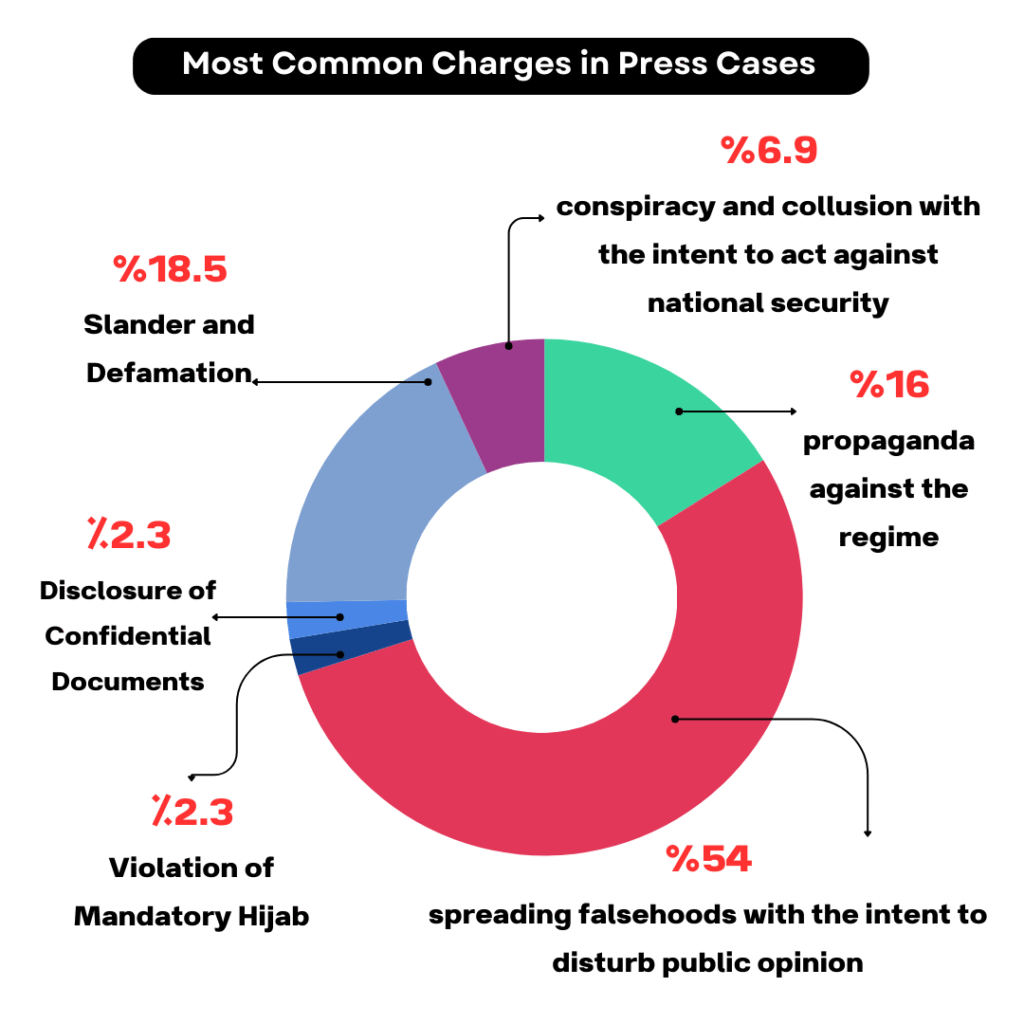

In the cases filed or rulings issued during this period, “spreading falsehoods with the intent to disturb public opinion” was the most frequent charge, attributed to journalists and media in 47 instances.

Additionally, “defamation and slander” with 16 instances, “propaganda against the system” with 14 instances, “assembly and collusion to act against national security” with six instances, “removing the hijab” and “disclosing classified documents” each with two instances, were the most recurrent charges in press-related cases.

According to cases documented by the Defending Free Flow of Information (DeFFI), judicial and security institutions violated the legal rights of journalists and media in at least 112 instances in the first half of 2025.

During this year, holding non-public press trials or trials without a jury in 45 cases and threatening, harassing, or deliberately disrupting the professional activities of journalists and media in 40 cases were the most frequent violations by the Islamic Republic’s judicial and security institutions.

Lack of access to a lawyer of choice, arbitrary detention of journalists and media activists, denying imprisoned or detained journalists family visits or phone calls, confiscating personal belongings or seizing journalists’ property without a judicial warrant, subjecting detainees to psychological torture, physical assault on journalists by judicial officers or individuals affiliated with government or security institutions, and media seizures were among other violations by judicial and security institutions in press-related cases during the first half of 2025.

To access the full details of this report, compiled in 68 pages, refer to the PDF file. This report is prepared in Persian.