In 2025, Iranian journalists and media outlets experienced an unprecedented period of intensified security pressures, judicial actions, and deliberate disruptions to their professional activities. In this year, Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, instructed the regime’s propaganda apparatus to adopt a “military posture”—a directive that openly illustrated the emergence of a securitized media environment in Iran. In this environment, an unequal contest exists between the Islamic Republic’s propaganda machinery and independent narrators of events.

According to findings documented by the Defending Free Flow of Information Organization (DeFFI), restrictions on freedom of expression in Iran escalated significantly in 2025. Patterns of suppressing independent reporting inside the country expanded, while transnational threats against Iranian journalists abroad rose to alarming levels.

Historic events in Iran and the broader Middle East, successive crises within the country, and growing public discontent activated the mechanisms of suppressing free information more forcefully than ever before. These events demonstrated a clear correlation with the increased repression of Iranian journalists and media.

The year 2025 coincided with the “12-Day War” between Iran and Israel, and in the final days of the year, widespread anti-government protests erupted across the country in a short period. The most extensive suppression of free information flow in 2025 occurred concurrently with the 12-Day War. This included the disconnection of international internet access, a sharp rise in judicial and security measures against media, journalists, and social media users, and the criminalization of Iranian citizens’ contacts with opposition media outlets abroad—all actions taken by the Islamic Republic to restrict freedom of information.

The Islamic Republic’s measures during the 12-Day War served as an effective rehearsal for the most unprecedented information blackout in its history, implemented in the opening days of 2026.

With the start of 2026, the Islamic Republic’s initial response to citizen protests was an unparalleled disruption of free information flows and the imposition of digital darkness across Iran. The government severed international internet connectivity, halted domestic and international telephone communications, and caused widespread interference across all communication networks in the country.

Statistical analysis and event documentation by the Defending Free Flow of Information Organization indicate that a significant portion of the judicial, security, and propaganda institutions’ responses to challenging events follow pre-designed patterns. The repetition of these suppression patterns in similar events—combined with the development and adaptation of certain patterns, particularly in response to anti-government protests—demonstrates that the mechanism for suppressing independent information in Iran is highly organized and that these protocols are continuously updated.

At the same time, the Islamic Republic appears to be gradually implementing an integrated system of media outlets, media activists, and quasi-media entities to execute its propaganda policies. This system encompasses state television and radio (IRIB), newspapers, news websites, and pro-government media activists inside Iran, along with tens of thousands of Telegram channels, Instagram pages, and Twitter/X accounts. Abroad, the repetition of the Islamic Republic’s narratives through a significant number of media activists, political figures, and academics points to a sophisticated system of extraterritorial propaganda operated by the Iranian government.

In 2025:

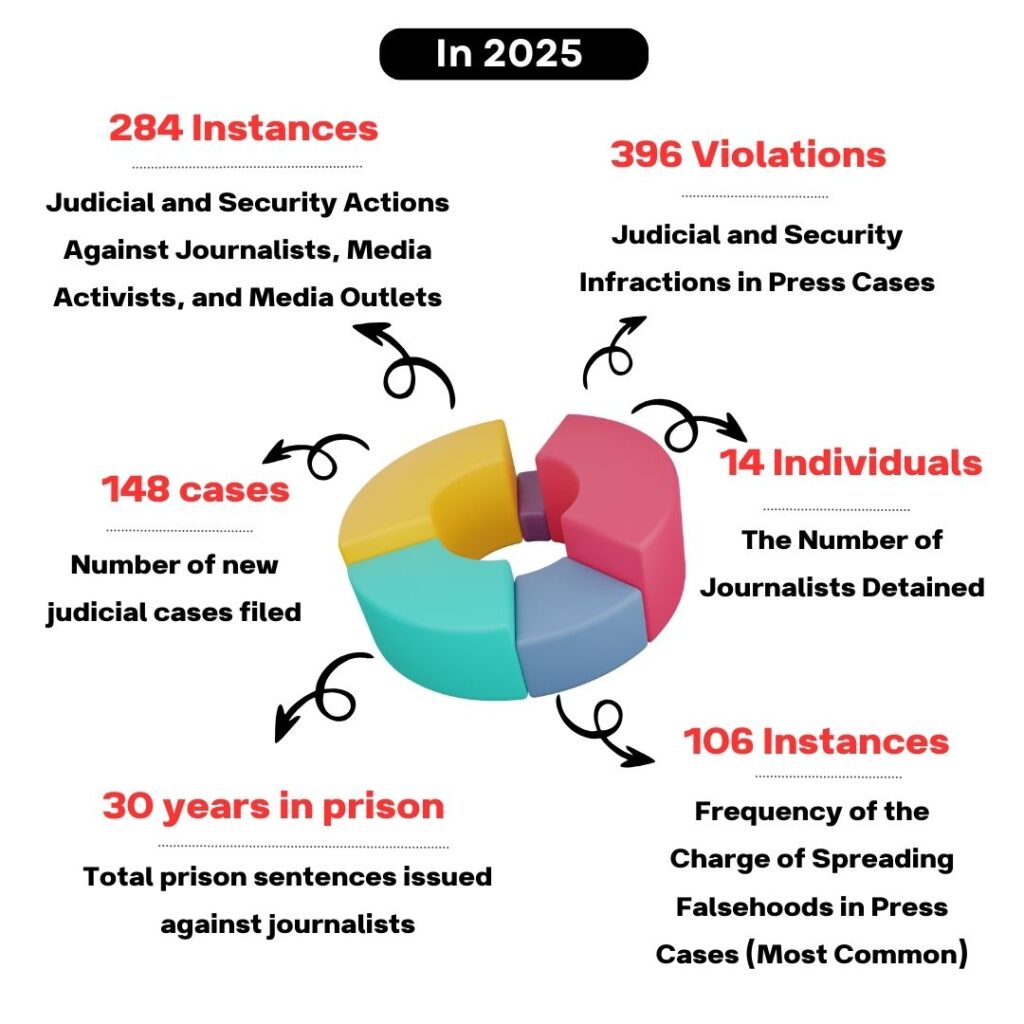

- 225 journalists and/or media outlets experienced judicial and/or security measures.

- At least 14 journalists were detained or had prison sentences enforced against them.

- At least 148 new judicial cases were filed against journalists and media outlets.

- Eight media outlets were shut down or banned.

- At least 34 female journalists faced judicial and security measures.

- Against 25 journalists or media managing editors, sentences totaling more than 30 years and 8 months of imprisonment, 293 million tomans in fines, and 5 years of exile were issued.

- Judicial and security institutions violated the legal rights of journalists and media in at least 396 instances.

- “Spreading falsehoods” ( نشر اکاذیب) was the most frequently attributed charge, used in 106 cases against journalists and media outlets.

Statistical Analysis of Systematic Violations of Media Professionals’ Rights

The Defending Free Flow of Information Organization (DeFFI) prepared its annual report based on 264 newly documented cases by its researchers. In 2025, DeFFI increased its share of total documented reports from primary sources on press suppression in Iran to 29 percent. This report was prepared with the support of Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

The year 2025 began with the continued imprisonment of at least 9 journalists in Iranian prisons. Nasrin Hassani in Bojnurd Prison, Zhina Modarres Gorji in Sanandaj Prison, Shirin Saeedi, Vida Rabbani, Saeedeh Shafiei, Rouhollah Nakhaei, Mostafa Nemati, Reza Valizadeh, and Cecilia Sala (the Italian journalist) entered the new year in Tehran prisons. The number of imprisoned journalists at the start of 2025 increased by three compared to the same period in 2024, when six journalists were held in Iranian prisons.

Throughout 2025, at least eight imprisoned journalists were gradually released. However, these releases did not signify a return to professional journalistic work in the country. All of these journalists faced serious restrictions on continuing their professional activities.

Over the course of the year, at least 14 Iranian journalists experienced temporary detention or were arrested to serve prison sentences. Mehrdad Aladin, Ali Pakzad, Majid Saeedi, Hossein Maleknejad, Parviz Sedaghat, and Mehdi Beyk in Tehran; Vahid Dalije in Golestan Province; Babak Amini in Khuzestan; Meysam Rashidi in Ardabil; and Hassan Abbasi in Kerman were detained and later released after a period.

Midway through the year, Azhdar Piri, editor-in-chief of the monthly Pazhuhesh Mellal, was arrested to serve his prison sentence and transferred to Karaj Central Prison. After approximately four months in custody, he was released following the conversion of his sentence to a suspended one.

In the final days of 2025, Aaliyeh motalebzadeh, a news photographer, was arrested in Mashhad. Ms. Motalebzadeh entered 2026 without any information available regarding her place of detention or the detaining authority. Despite suffering from cancer, this photographer was held in solitary confinement and denied access to necessary medications and effective medical care.

At the end of 2025, two journalists remained imprisoned in Iran: Reza Valizadeh in Tehran’s Evin Prison and Aaliyeh motalebzadeh in an unknown detention facility in Mashhad.

In 2025, the suppression of Iranian journalists and media continued unabated. In just one year, 225 journalists and/or media outlets faced judicial and/or security measures, and at least 148 new judicial cases were filed against journalists and media. Prosecutors initiated more than half of the cases filed during this period. Following prosecutors, government officials and institutions ranked next, with private individuals or companies coming after them as complainants against journalists and media.

Similar to 2024, the most frequent trigger for judicial and security measures against journalists and media in this period was criticism of the Islamic Republic’s inefficiencies or the publication of reports on corruption involving institutions and government officials. Publishing reports or social media posts criticizing the Islamic Republic’s international and regional policies—particularly regarding Iran-U.S. negotiations and the Iran-Israel war—as well as reporting on the explosion at Bandar Rajaee Port, were among the other most common grounds for filing judicial cases or imposing security measures on journalists and media.

In the trials held during this year, against 25 journalists or media managing editors, cumulative sentences of more than 30 years and 8 months of imprisonment, 293 million tomans in fines, 5 years of exile, 6 years of prohibition from journalistic activities or social media engagement, and 4 years of travel bans were issued.

The harshest sentence issued in 2025 was against Reza Valizadeh. In January 2025, Tehran’s Provincial Court of Appeal sentenced this Iranian-American journalist to 10 years in prison, 2 years of prohibition from residing in Tehran Province, 2 years of travel ban, and 2 years of prohibition from membership in political parties or groups. Reza Valizadeh, a political prisoner held in Evin Prison and former correspondent for the Persian service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Radio Farda), remains incarcerated.

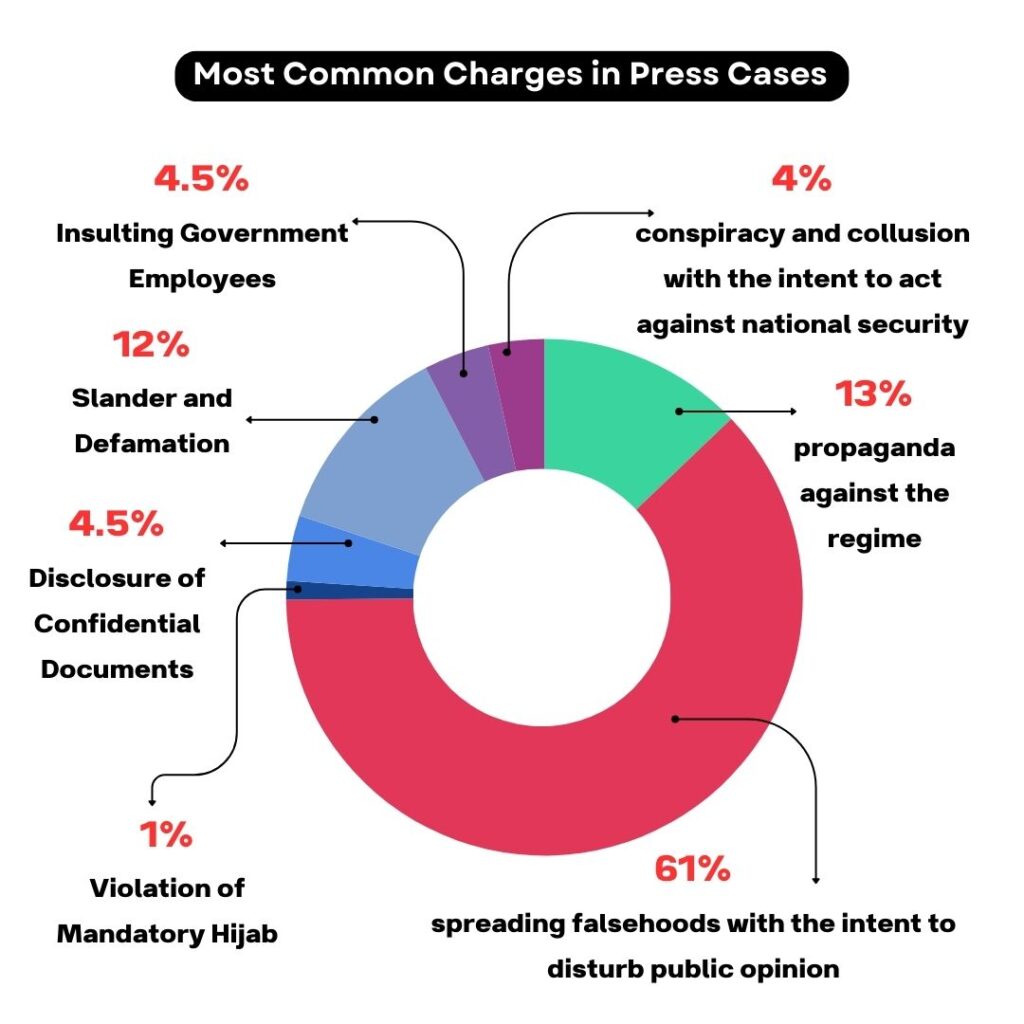

According to the Defending Free Flow of Information Organization (DeFFI) database, in the cases filed or sentences issued in 2025, “spreading falsehoods with the intent to disturb public opinion” (نشر اکاذیب با هدف تشویش اذهان عمومی) was the most frequently attributed charge against journalists and media, recorded in 106 cases.

The repeated use of this charge in press cases appears to stem from two main factors. The first is Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, who has repeatedly called for “action” against journalists, media, and independent narrators using the keyword phrase “disrupting society’s psychological security.” Following each of Khamenei’s speeches, the Islamic Republic’s judiciary initiated a new wave of judicial measures against journalists and media. The second factor is the deliberate effort by judicial and security institutions to discredit independent reporting in Iran.

In 2025, other frequently repeated charges in press cases included “defamation and slander” (21 instances), “propaganda against the system” (22 instances), “insulting government employees” (7 instances), “disclosing classified documents” (7 instances), “assembly and collusion to act against national security” (6 instances), and “establishing or managing an illegal group,” “cooperation with hostile governments,” and “removing the hijab,” each with 2 instances.

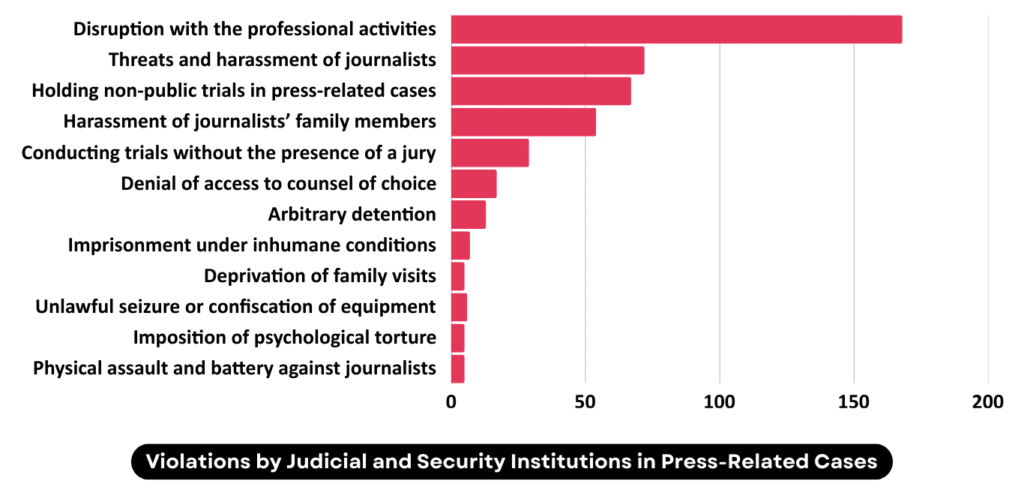

In the cases documented by the Defending Free Flow of Information in 2025, judicial and security institutions violated the legal rights of journalists and media in at least 398 instances.

Threats, harassment, and deliberate disruption of journalists’ and media professionals’ activities (239 cases), holding non-public trials in press cases (67 cases), and threats and harassment of journalists’ families (54 cases) were the most frequent violations committed by the Islamic Republic’s judicial and security institutions.

Other violations in press cases during 2025 included holding press trials without a jury, arbitrary detention of journalists and media activists, imprisonment under inhumane conditions, denial of access to chosen legal counsel, depriving imprisoned or detained journalists of family visits or phone contact, seizure or confiscation of journalists’ personal belongings without judicial orders, psychological torture of detainees through prolonged solitary confinement, physical assault on journalists by judicial officers or individuals affiliated with government and security institutions, and extralegal seizure of media outlets.

Disruption of Free Information Flows and the Development of Patterns of Suppressing Freedom of Expression

The mechanisms for suppressing free information in Iran underwent a tangible and meaningful change following the start of Masoud Pezeshkian’s presidency. These mechanisms became more complex and multidimensional. While certain longstanding patterns of repression—used prior to July 2024 (the presidential inauguration ceremony)—continued, newer patterns gradually became more frequent.

Threatening phone calls from security institutions—particularly IRGC Intelligence—escalated sharply compared to the pre-Pezeshkian period. This pattern led to a relative decrease in the number of summonses, new judicial cases, or arrests of journalists compared to the equivalent period before.

At the same time, the extralegal deactivation of mobile SIM cards emerged as another widespread tactic employed in 2025 against Iranian journalists and political activists—more intensively than in previous years. In this pattern, mobile network operators disabled citizens’ SIM cards without judicial orders and without prior notice.

Although several journalists told Defending Free Flow of Information (DeFFI) that they were unaware of which entity had deactivated their SIM cards, DeFFI research revealed that the deactivation of SIM cards belonging to political activists and journalists in Iran is primarily carried out on the orders of the Cyber Security Command of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (Gerdab), an entity affiliated with IRGC Intelligence.

Concurrently, the blocking of journalists’ and independent narrators’ accounts on social media platforms—without judicial warrants—along with the imposition of restrictions on these platforms and intensified security pressure to force the deletion of critical posts, became another frequently repeated pattern in 2025.

Pressure on media managing editors to prevent the preparation and publication of challenging reports, combined with the allocation of extensive financial resources to co-opt media outlets and journalists into the Islamic Republic’s propaganda projects, was another pattern applied more intensively in 2025 than in previous years.

Filing criminal complaints by prosecutors against media outlets, journalists, and independent narrators remained one of the most recurrent patterns of suppressing freedom of expression in Iran in 2025—a pattern that escalates exponentially following major controversial events in the country.

Furthermore, findings by the Defending Free Flow of Information Organization (DeFFI) indicate that political and press courts in Iran once again systematically refused—in violation of the Press Law—to hear portions of media and journalist cases, referring most of these files for trial to Criminal Court Two and Revolutionary Courts in a deliberate pattern.

These newly frequent patterns appear to be designed to manipulate freedom-of-expression indicators and conceal the true scale of suppression of independent information flows in Iran. As a result of these evolving repression mechanisms, traditional metrics—such as the number of imprisoned journalists, the volume of press cases, the number of banned media outlets, financial independence of media, and similar indicators—can no longer fully capture all dimensions of the disruption to independent information in the country.

For this reason, alongside traditional indicators, the Defending Free Flow of Information Organization (DeFFI) now employs the metric of “instances of judicial and security measures” to record the various forms of suppression of independent information flows. This indicator registers all patterns of interference in the professional activities of journalists and media outlets as violations of media professionals’ rights.

The combined effect of these new repression patterns—alongside longstanding ones previously used against Iranian journalists and media—drove freedom-of-expression indicators in Iran in 2025 to an unprecedented low.

Numerous interviews conducted by DeFFI with Iranian journalists reveal that targeted judicial and security measures have led to widespread self-censorship among media professionals. Many media activists refrain from expressing opinions or publishing challenging reports in numerous instances due to fear of judicial and security persecution.

The Islamic Republic also seeks—through the continuous filing of cases against media outlets and their managing editors—to compel media to self-censor and remain passive, while indirectly turning a portion of managing editors into tools of pressure against journalists.

Iranian journalism is experiencing extremely difficult and alarming conditions—conditions that are not solely the result of judicial and security measures. The absence of cohesive journalistic associations and severe financial crises in media outlets are additional factors exacerbating this unacceptable situation.

In 2025, no steps were taken to reopen the Iranian Journalists’ Union (closed following the 2009 protests), and state interference in press independence continued through the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance’s complete control over a significant portion of media financial resources (distribution of advertising allocations).

While weakening independent journalism inside Iran, the Islamic Republic has simultaneously made massive investments in its own propaganda apparatus. Security, judicial, and propaganda institutions of the Islamic Republic work in close coordination to prevent independent narratives from becoming dominant among the public.

The goal of the Islamic Republic’s propaganda apparatus is to impose official narratives on public opinion. Security and judicial measures against media, journalists, and publishers of unofficial narratives are efforts to block the widespread dissemination of these narratives, discredit independent accounts, and—in some cases—generate multiple parallel counter-narratives. This remains the most recurrent pattern of suppressing free information flows in Iran.

At the same time, through state television, nationwide newspapers, quasi-media entities, pro-regime media activists, and regime-supporting users on social media, the Islamic Republic organizes large-scale campaigns to disseminate fake or misleading news and reports. These campaigns aim to prevent challenges to the official narrative or to diminish the impact of independent accounts.

In Iran, a large portion of information remains monopolized by state institutions. Many citizens are deprived of access to reliable and timely information. Numerous events lead to public confusion and ambiguity, and society faces serious difficulties in analyzing realities and making informed decisions. These conditions are, above all, the product of systematic and organized disruption of free information flows in Iran.

This report has been produced with the support of Reporters Without Borders (RSF). It was elaborated in accordance with the methodology of the Organization for the Defending Free Flow of Information (DeFFI) and comprises 101 pages. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of RSF. The complete report is available in the attached PDF document.